Sustainable Future Cities, Towns and Communities (III)

“Cities have a unique role and opportunity to shape humanity´s chances of thriving in balance with the rest of the living planet this century.” (Doughnut Economics Action Lab)

The thinking behind the above quote by the Doughnut Economics Action Lab is challenging our understanding of local economic development in many ways. What makes a local and national economy healthy, thriving, respectful towards other communities worldwide, regenerative and redistributive? What kind of understanding of local economic development and action is needed to promote local living conditions within our planetary boundaries for the majority of citizens? How does one make the best use of the available material and knowledge resources for a decent development path?

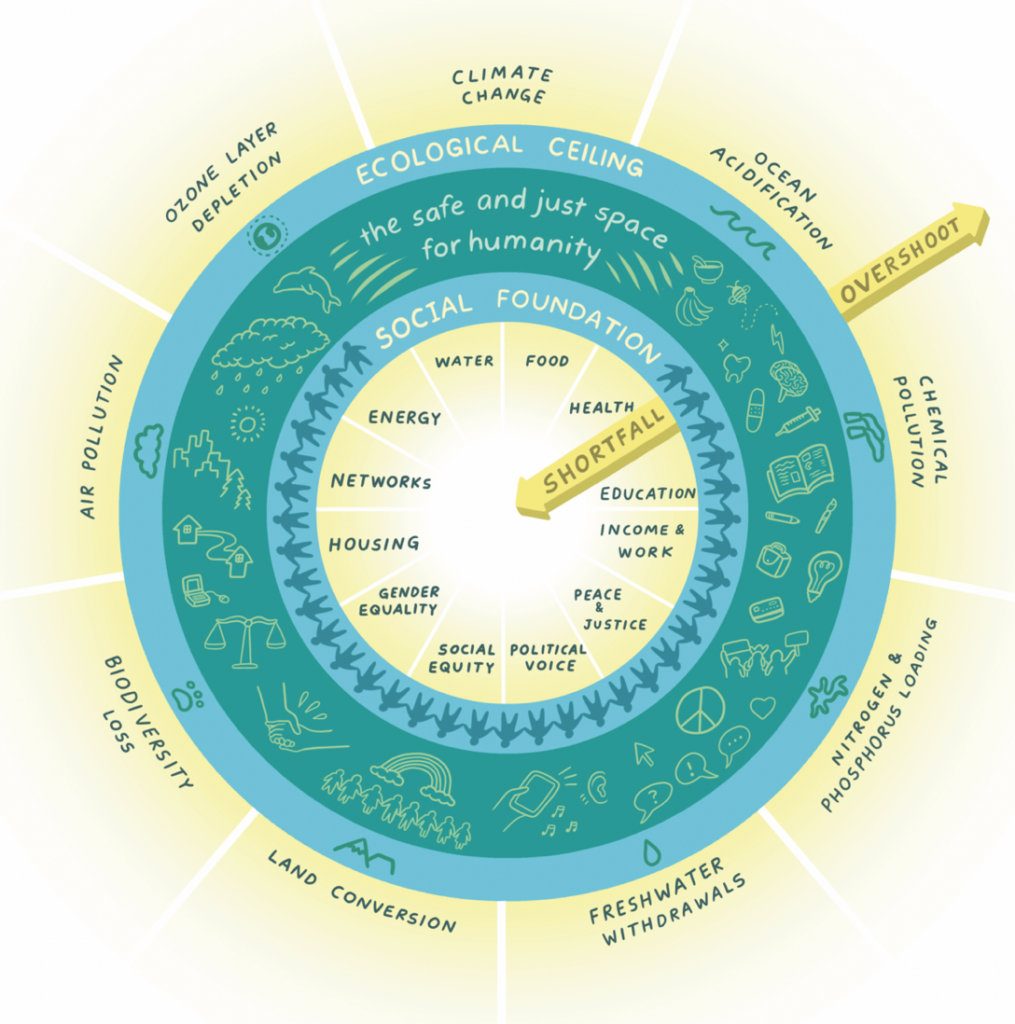

Figure 1: The Doughnut model

The Doughnut Economics perspective, as well as the activities of the Doughnut Economics Lab in very different cities, provides much food for thought. They challenge us to rethink our own practice. This blog will provide us with the opportunity to better understand the thinking framework of the Doughnut Economics approach by Kate Raworth. We will then go on in another Blog (coming soon) to look at how this thinking is applied in the existing City Doughnut initiatives and what it entails regarding practical insights and instruments for our own practice in promoting transformative local economic development.

Two reasons why the Doughnut has drawn international attention

The “Doughnut Economics” publication by the British economist Kate Raworth has drawn international attention since its publication in 2017, both from the climate change movement and from academia. The approach has become emblematic of new economic thinking for two main reasons:

1) Raworth challenges the mindset of traditional growth-driven economic models and their linear notion of healthy wealth creation because they have never factored in environmental and social costs.

2) She calls for and promotes a more “healthy”, “embedded” and “thriving” economic development approach in which the relevant indicator is not GDP but a healthy balance between ecological, social and economic progress.

Under the following three headings we will briefly present the general doughnut framework, its logic, and the key aspects and values that drive it. Finally we will present questions which we have not often asked ourselves before, but the answers to which are necessary for a transformative local economic development perspective.

I. The Doughnut framework

In her doughnut approach Raworth combines the planetary boundaries developed by leading Earth system scientists in 2009 (such as Johan Rockström (2009), Will Steffen and others) with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The idea of the doughnut is simple: there are two rings. The outer ring symbolises the global ecological ”ceiling“. Beyond the ceiling lie the nine planetary boundaries, so-called ”tipping points“ and unacceptable environmental degradation such as climate change, ozone layer depletion and a decline in biodiversity. The inner ring represents the social foundation, consisting of the SDG’s minimum social standards such as food, health or gender equality, to ensure that all people have access to the basic needs of life (see details in figure 1) .

The space between the two rings or boundaries — the “substance” of the doughnut — is the “safe and just place for humanity“, representing a ”safe zone“ in which the local society and the global society are encouraged to thrive economically, with social foundations or basic needs being met for all people. The task is to bring humanity into this safe and just space and to prevent either ecological overshoot as well as social “undershoot” or developmental shortfall.

II. Key aspects of the doughnut

There are some key terms used in the Doughnut approach which also provide a deeper understanding of its direction (see figure 2):

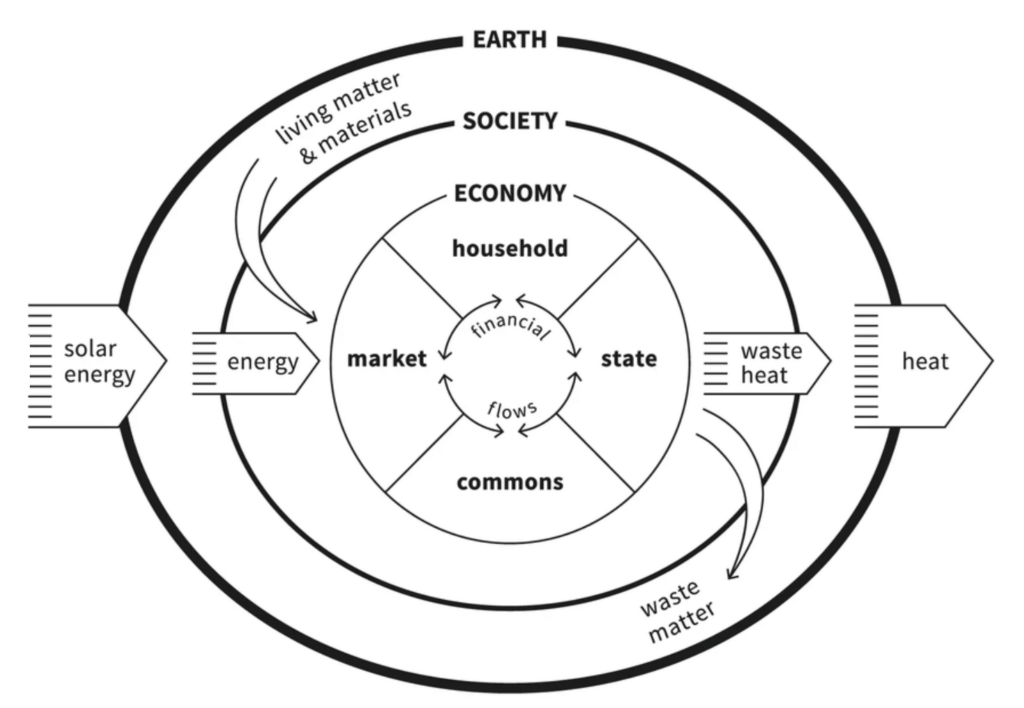

Figure 2: The embedded economy

- The model of the embedded economy, “which nests the economy within society and within the living world, while recognizing the diverse ways in which it can meet people´s needs and wants” (Raworth, 2017: 71). The term “embedded” means not only that development is embedded in the two rings of the doughnut. In contrast to classical economic models, which mainly focus on free-market forces (with their businesses acting in their realm) and the state acting as a regulating and distributing factor, it also embeds households and the commons as core economic factors and prerequisites for the formal economy. By not valuing the unpaid daily household work (including subsistence and parts of informal sector work, often still dominated by women) and by not valuing common goods that create value for many communities and individuals, the chance of understanding the opportunities for a thriving economy is lost. We highly recommend reading Raworth’s arguments on these aspects to deepen sensitivity.

- The understanding of a thriving economic development path in contrast to a growth-driven path: Raworth argues that the goal for economies should be changed from growth (as measured by GDP) to thriving economies (local, regional and national). The thriving economy acts within the safe space of the doughnut. It symbolises a very dynamic place that makes full use of the economic and social development opportunities in a country or a city. This also involves redistributive efforts to increase access to education, technology, knowledge, creativity and innovation skills for individuals, households, the commons and businesses. It asks for a responsible and sustainable development-oriented government role. Use of the unmet potentials in these fields provides key opportunities for a thriving economy.

- A circular economy regenerative by design: A regenerative resource model is a key element of the doughnut. In contrast to the dominant fossil-fuel-based and linear (degenerative) production and consumption system (take-make-use-dispose), a thriving and embedded economy needs to make use of a circular system with a regenerative character (reduce-reuse-recycle-recover). It provides the health and wellbeing of the system.

- Overcoming an isolated local or national economic perspective, but taking the economy of the society and even the world economy as a reference framework: the doughnut model does not stop at the city or national level. It also requires a global perspective. In this respect it asks for responsible local and global behaviour from citizens, businesses and governments. This also requires the promotion of economic and political action that promotes healthy local and global chain relations vs. unhealthy relations and production models.

- The leading responsibility of industrialised countries: Raworth (2017: 245) asks for an agnostic perspective of GDP growth “in the sense of designing an economy that promotes human prosperity whether the GDP is going up, down, or holding steady.” Her focus here is especially on industrialized countries and middle-income countries, where growth models have for a long time been built at the expense of the planetary boundaries. For many developing countries GDP growth will still be necessary to escape the poverty trap. Nevertheless, here the doughnut asks for international support to leapfrog the polluting technologies. The national responsibility is to channel the GDP growth into creating economies that are distributive and regenerative by design with the objective of reaching high social and ecological living standards within the safe space of the doughnut (Raworth 2017: 254).

- Addressing and developing the multiple facets of humans as economic and social beings: For us one of the most essential elements of the doughnut is its underlying interpretation of humans as transcontextualbeings (Bateson 2016). It criticises the simplistic understanding of humans as rational and selfish beings and rather sees and values them as multiple beings with many social and economic identities: “In the household we may be parents, carers and neighbours. In relation to the state we are members of the public, using public services and paying taxes in return. In the commons we are collaborative creators and stewards of shared wealth. In society we are citizens, voters, activists and volunteers. Every day we switch almost seamlessly between these different roles and relations.” We think that this more complexity-sensitive and multiple or transcontextual understanding of humans also needs to shape a new way of how to promote economic development. As Nora Bateson expresses it (quoted from a blog post by Marcus Jenal: “The complexity of our approaches needs to meet the complexity of the problem we are trying to tackle.”

III. Questions the doughnut raises for local economic development practitioners

The upcoming Blog 2 will dive deeper into the city doughnut approach and ways on how to promote these perspectives in our own work at the local level. Nonetheless, before moving on to that it is necessary to ask ourselves some critical questions when looking at our world interpretation in our daily work, taking the doughnut logic as a reference point:

- To what extent have we as economic development practitioners really looked into our promotion activities on the boundaries of the Earth system, and have we also analysed more deeply the ecological impact of the suggested business support measures, locally and also worldwide?

- While promoting existing businesses, investors and start-ups, value chains and clusters in different locations, to what extent have we also considered and analysed their interwoven social impact within the national and global economy?

- When promoting business networks, supporting organisations, policy development, etc., what was our understanding of human beings in this respect? Did we address and involve them in their transcontextuality or multi-identities, or did we see them mainly as economic actors?

- Local economic development is a lot about strengthening the commons, promoting networks to increase the attractiveness and life quality of the place. We often emphasize the need for co-creation, making use of and promoting synergies between different knowledge sources. Even so, did we also look at those commons that are less directly related to business or locational advantages but to common social goods that contribute beyond employment and income?

- What was our understanding of a thriving economy? Households rarely turned up, maybe only when we were looking at the informal sector and household production efforts in some developing countries. But in general, we separated survival activities from economic activities, survival entrepreneurs from entrepreneurship-driven entrepreneurs. Is knowledge and innovation promotion still not mainly focused on entrepreneurs, often male, and not involving an environmental and social innovation perspective in which citizens and households as core economic bases play an important creative role?

- Do we still measure the success of our work mainly along growth indicators, or do we also measure it alongindicators that are related to human prosperity and human development?

A deeper reflection on these issues in our field of work is much needed. It asks for a new, broader understanding of innovation and development in business development. It challenges us to unleash creative potential not only in companies but also in society. We also see this as an opportunity for more humane and transformative approaches in our work. Every online reflection and all comments to these questions are highly appreciated.

In the next blog we will also present some practical examples and selected tools from the Doughnut Economics Action Lab that we find very useful to start with in our own practice.

Guido Zakrzewski und Frank Waeltring

References

Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut economics, seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. London: Penguin Random House.

Rockström, Johan (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461: 472-475.

Bateson, Nora (2016): Small arcs of larger circles: framing through other patterns. Axminster, UK: Triarchy Press.

Other Blogs of the series